A major question of leadership is “Can Leadership Be Taught?” This question stems from the idea that initially, anything that is taught may only be understood in the mind. And our mind is a “meaning-making machine” so it immediately starts by trying to understand new ideas by creating associations with things it thinks it understands. Thus, learning something new – like flying an aircraft, without previous or worse, different associations, is difficult.

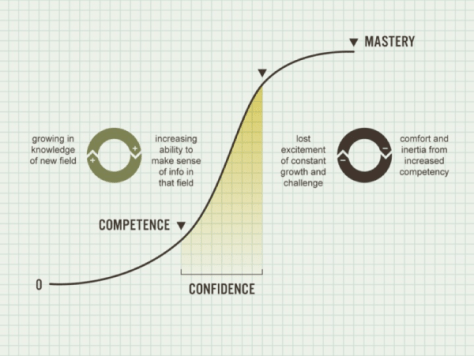

Being playfully Socratic is to ask “whether something that exists only in the mind actually exists at all?” I only pull this thread because until I experience something physically or emotionally in combination with the intellectual, does it become understood within me. Therefore, I have found that teaching leadership, or anything else, requires the student to experience it themselves. So, NO, leadership cannot be taught, it must be learned. Brian Johnson expresses his learning philosophy in the statement “Theory to Practice to Mastery.” Thus it is the practice and the work toward mastery that takes us to learning.

A major question of leadership is “Can Leadership Be Taught?” This question stems from the idea that initially, anything that is taught may only be understood in the mind. And our mind is a “meaning-making machine” so it immediately starts by trying to understand new ideas by creating associations with things it thinks it understands. Thus, learning something new – like flying an aircraft, without previous or worse, different associations, is difficult.

Whether purposeful or not, the Air Force has developed its flight training around these ideas. Each phase begins in the classroom, where we are taught an aspect of training. We learn physiology, weather, aircraft systems, normal and emergency procedures, “contact” flying, instruments, formation training, etc. But then, it is taken out of the classroom.

For example, we are taught ejection procedures; a really important subject for a really dangerous moment. Something that, through thousands of practice iterations, it is deeply ingrained in my subconscious. Something I was fortunate to ever have had to execute; but have many friends who have.

The boldface for ejection in the T-37 was “handles pull, triggers squeeze.” Seems like a relatively benign statement; but if you were in an unrecoverable spin, where a second of delay might mean death, it is important.

When I was training in the RF-4C, a student put the jet out of control and delayed ejection. The backseat WSO initiated the ejection late; because of the ejection sequence, he was saved but the pilot was lost.

In a similar example, one of my good friends was landing an RF-4C with a broken hydraulic line to an aileron, making the aircraft roll unstable. As he approached the runway threshold, he unconsciously added the normal small inputs to stabilize the aircraft and it began to roll wildly. The WSO was quick to see a diminishing window of opportunity and successfully ejected himself and the pilot as the aircraft tumbled down the runway. The pilot, “Ironman,” left the aircraft a few feet above the ground, basically ejecting sideways with his parachute blooming horizontally as it set him on the ground.

The legend (and we made it a legendary bar story) is that the WSO ran over to him so quickly, that he was laying on the ground in the fetal position, still trying to fly the non-existent aircraft; with his legs moving as if he was running a sprint. Thank God the WSO had the capacity and training to eject them within a nano-second of opportunity.

In order to obtain this capacity, we had to do more than simply be taught to eject.

Back to pilot training, before we could initiate the ejection boldface, you had to get into an ejection position, to avoid breaking your back or hitting your feet during the 20 Gs you would feel being propelled out of the aircraft, yell “bailout, bailout, bailout” and pull the handles.

Then, the life-support trainers would sit you into a mock cockpit and you would practice “ejecting.” This unique seat was special as it would shoot you up a hydraulic pole about six feet to ensure you experienced the first moments of a real ejection (at a much lesser actual G-loading). Doing this scares the bejeezus out of you, so you capture the lesson quickly, avoiding the need to do it twice.

Next, they hang you in an ejection harness as if you were floating in a parachute. The trainers take you through a sequence I remember today. Canopy, Visor, Mask, Seat Kit, LPU, 4-Line, Steer, Prepare for PLF (parachute landing fall), look to the horizon and hit the ground. And there were a set of procedures for trees, powerlines, water, etc. Once landed, there is another entire set of activities based on peacetime training or combat ejection. Mostly, “drink your water” and take a breath.

Back to pilot training, after sitting in the harness, they would send you outside where you practice your PLF into “pea” gravel. You started by falling into it, then you jump off a one-foot platform and work yourself up to three feet. Finally, they would re-harness you to a rope and parachute where a jeep would pull you airborne so you could practice your landing. Although very serious, we would laugh as each student would strive to provide a meaningful antic to outdo the previous one. I remember K+10 splitting his legs into a set of splits, as that became drinking lore for the rest of UPT.

So the Air Force recognized that learning takes place beyond the mind. And even though I went through ejection seat training in 1988, almost 35 years ago, and certified annually, I never used it; but know it viscerally!